The Price of Truth

In 1945, while the world was still sorting through rubble after World War II, an Austrian economist published a twelve-page paper that would quietly outlast most of the century's grand political projects. Friedrich Hayek's The Use of Knowledge in Society asked a question so fundamental that most economists had simply assumed it away: if the knowledge needed to run an economy is scattered across millions of minds, and much of it can never be written down or transmitted to a central authority, then how does coordination happen at all?

The answer, Hayek argued, is the price system. And understanding why he was right, what it takes to keep him right, is the key to understanding why prediction markets work, why experts with credentials keep losing to gamblers with money on the line, and why truth isn't something you reason your way to, but something that costs you to be wrong about.

The knowledge problem is not about intelligence. Central planners are not inherently stupid. However, Hayek provided something more devastating: the kind of knowledge an economy runs on cannot, by its nature, be centralized. It does not matter how smart the planner is. The knowledge simply cannot exist in a form that can be collected.

Hayek drew a sharp line between two kinds of knowledge. The first, scientific knowledge, is the kind you find in textbooks and databases. It can be gathered, organized, and handed to a committee of experts. This is the kind of knowledge that makes central planning seem plausible. If the problem were only about scientific facts, a sufficiently powerful AI (or a sufficiently large bureaucracy) could theoretically solve it.

But the second kind, what Hayek called the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place, is different in nature. This is the knowledge possessed by the Grab driver who knows which shortcut to take during a rainy Friday's rush hour, the real estate agent who knows which properties are underused, the factory manager who knows that Machine No. 3 runs slower on humid days. It is the practical wisdom (phronesis) that exists only in the heads of the people closest to the situation that changes minute by minute, and often can't even be articulated, let alone transmitted to a central authority in statistical form.

This was Hayek's real strike against the socialist calculation debate. Economists like Oskar Lange had argued that a central planning board could, in principle, replicate market outcomes by gathering all the relevant data and solving the allocation problem mathematically. Hayek's response was that the data does not even exist until someone acts on it. This knowledge of particular circumstances can never enter into statistics. A central authority that tried to collect it would have to abstract away the very details — location, quality, timing, local conditions — that make this knowledge useful.

So what solves the problem? The price.

Hayek used a famous thought experiment. Suppose somewhere in the world, a new use for tin has been discovered, or one of the sources of tin supply has been eliminated. It doesn't matter which. All that matters is that tin has become scarcer. Users of tin don't need to know why. They don't need to know whether the cause was a mine collapse in Bolivia or a new semiconductor process in Japan. All they need to know is that tin has become more difficult to procure relative to other things. The price tells them exactly that. They act and look for substitutes, or shift resources. This cascade ripples outward through the entire economy, first through the substitutes of tin, then the substitutes of those substitutes — all without anyone issuing an order, and without the vast majority of people involved knowing anything at all about the original and correct cause of the change.

Hayek called this a marvel. I believe it. A single number, the price, compresses into itself the dispersed knowledge of thousands of people, transmits it across the entire economy, and coordinates behavior that no central planner could have directed. Each individual needs to know almost nothing about the wider system. They only need to watch a few prices, the way an engineer watches a few dials, and adjust accordingly.

But the price is only as honest as the people who set it. So how does Hayek's mechanism enforce itself?

Enter Nassim Taleb, and the question no one was asking: what determines the honesty of a price signal?

Hayek showed that prices aggregate dispersed knowledge. But he largely assumed that the people participating in the price system were operating with genuine exposure to the consequences of their decisions. The shipper filling his steamer, the arbitrageur exploiting price differences between markets; most of these people had their livelihood dependent on being right.

Taleb made this enforcement mechanism explicit. The core argument of his idea, the Skin in the Game, isn't just that people should face consequences for their decisions. In reality, consequence is the only reliable mechanism for producing accurate information in the first place. Without it, you get what Taleb calls the "Bob Rubin trade": people who capture the upside of their bets while quietly transferring the downside to others. Bankers who collect bonuses in good years and invoke "unprecedented events" when the hidden risks they took blow up (yet they suffer no consequence). Foreign policy advisors who advocate for wars they personally never fight in. Economic and political forecasters in academia who are wrong year after year but keep their columns and tenure. Urban planners designing transport systems they never actually ride.

Taleb's famous line cuts to the point: Don't tell me what you think. Tell me what's in your portfolio.

It's not just a witty jibe. The principle is simple but deep. Stated preferences and revealed preferences are fundamentally different things. What someone says they believe, when they face no consequences for being wrong, is cheap talk. What they do with their own money, their career, their time, their reputation — that is the information. A poll asks a thousand people what they think will happen. A market asks a thousand people to put money where their mouth is. These are not even remotely close, and they should not be expected to produce the same results.

Taleb goes one step deeper. His real argument includes survival as an information mechanism.

Let us first consider how the financial markets, or even casinos actually work. It's not just that bad bettors lose money. In fact, they are removed from the system entirely. A trader who consistently misprices risk doesn't just take losses. He eventually hits portfolio ruin and zeroes out. The poker player who overplays his hands loses all his chips.

They cross what Taleb calls the absorbing barrier: the point of no return from which there is no recovery. And once they are gone, their bad information is gone with them. The market's signal improves not because people learn from mistakes, but because the system filters out the people who make them. For the casino, the ruined player's chips transfer back to the house as profit, subsidizing the system.

This is what Taleb calls via negativa (or "what not to do") applied to knowledge. Systems learn by removing parts, and not by adding extra things. For example, many bad pilots are at the bottom of the ocean. Many reckless drivers are in quiet cemeteries. Aviation itself as an industry did not get safer primarily because individual pilots learned from errors. It got safer because the system eliminated the ones prone to fatal errors, and the survivors, as well as the institutions that trained them, carried forward better practices. The experience of the system is fundamentally different from the experience of individuals and is grounded in filtering.

When applied to markets: the people still standing in a market after ten years of trading are the signal. Their continued survival is itself information about the quality of their judgment. The price they collectively produce is trustworthy not because each individual is wise, but because the unwise have been systematically purged. Survival talks the loudest.

Compare this to the world of expert prediction without skin in the game. A political commentator who called the 2016 election wrong, the 2020 dynamics wrong, and the 2024 landscape wrong is still on television making predictions in 2026. The scientist who was completely wrong on COVID and the futility of vaccines is still around on TV LARPing as "health experts". There is no absorbing barrier, no ruin. This system does not filter out the bad forecasters; in fact they are given deals and accolades by their peers! Knowledge produced by such a system, and in my opinion, much of modern academia, which does not filter signal from noise, is ultimately garbage.

In essence, Hayek says: dispersed knowledge can only be aggregated through a price mechanism, not through central collection. Taleb says: the price mechanism only produces honest signals when participants have skin in the game, because skin in the game creates the evolutionary filter — ruin — that removes bad information from the system over time.

What you get when you put these together is the theoretical foundation for prediction markets, and the single line that captures it: a dollar in a market is a weighted vote, where the weight is your conviction and your competence. Conviction, because you chose to risk money rather than merely state an opinion. Competence, because if you lack it, the market will eventually take all your money and you'll stop voting.

This is what makes platforms like Polymarket and Kalshi interesting. It is perhaps the purest implementation of the Hayekian mechanism we've ever built. A standard equity market prices a complex, multi-variable asset — the future cash flows of a company, discounted by risk, adjusted for a thousand other moving factors. A prediction market strips this entire mechanism down to a single binary question. Will this happen or not? And then it lets the price system answer.

In 2024's US election, when Polymarket showed Trump's odds of winning the election at 64% hours before the results while most polls had the presidential race as a toss-up, the instinct of many commentators was to call the market biased — skewed by crypto traders, or by Republican partisanship, or by the demographics of the platform's user base. This objection confuses the mechanism with the participants. The market was not "smarter" than the polls. It was structurally different. The polls sampled stated preferences from a representative or even biased population.

The market aggregated revealed conviction from people with enough local, dispersed knowledge to risk their own capital on the answer. These are fundamentally different exercises, and the Hayekian framework predicted exactly when and why they diverged.

This post is more than just an argument about prediction markets, because if you accept Hayek's premise and Taleb's enforcement mechanism, you will realize prediction markets are not a special case.

The broadest prediction market in the world is simply the free economy itself.

Every business is a bet. Every entrepreneur who raises capital, hires a team, and ships a product or service is a forecaster with maximum skin in the game. They are making a specific prediction: that this product or service will serve this market at this price point better than the alternatives. And they're backing that prediction with their money, their time, and very often their health and their relationships. If they're wrong, the market doesn't just give them a participation trophy and invite them back on the panel next quarter but punishes them heavily instead. The restaurant that mispriced its market closes. The startup that misread demand burns through its capital and dies. The venture fund that backed the wrong thematic thesis underperforms the market index and their LPs go elsewhere.

Free capital markets are, in this light, Polymarket scaled to the entire economy. The "price" of a company's stock is a prediction about its future, set by participants who have real money at risk. The "price" of a barrel of oil is a prediction about supply and demand, compressed into a number that coordinates the behavior of millions. The entrepreneur who opens a coffee shop on a particular street corner is placing a bet that incorporates knowledge no survey could ever effectively capture — the foot traffic patterns she observes at 7am, the construction project she knows is coming next quarter, the taste of the neighborhood she understands because she lives there. This is Hayek's knowledge of particular circumstances of time and place, expressed not through a report to a planning board, but through the act of risking capital.

Taleb himself makes this point about decentralization. It is easier to "macrobullshit" than to "microbullshit." A central planner can issue sweeping directives untethered from local reality because the feedback loop is slow and diffuse. However, a shopkeeper who bullshits about demand goes broke by the end of the quarter. Decentralization reduces the distance between the prediction and the consequence, which is another way of saying it increases skin in the game, which ends up making prices a more honest reflection of reality.

If the mechanism is so powerful, why does it ever fail?

To decipher this, we must first examine the nature of crowds and mob mentality.

James Surowiecki identified four conditions that must hold for crowds to produce accurate estimates: diversity of opinion, independence of judgment, decentralization of information, and a reliable aggregation mechanism. When all four hold, a crowd's collective estimate converges on truth with startling reliability, also known as the "wisdom of crowds" phenomenon (something that has endlessly fascinated me in my younger days).

The wisdom of crowds is famously illustrated by the 1907 story of Galton's ox, where statistician Francis Galton analyzed nearly 800 guesses for the weight of an ox at a county fair. While individual estimates varied widely, ranging from informed opinions to wild guesses, the final average of the entire crowd was 1,197 pounds, which was remarkably just one pound off the actual weight. This phenomenon demonstrates that a diverse collective can produce a near-perfect answer because individual biases and errors cancel each other out, offering a final "measure of the middle".

But Galton's ox had something most real markets don't necessarily guarantee: eight hundred strangers guessing independently, with no one watching anyone else's ticket. The conditions were perfect. When any of them break down, the crowd becomes a mob.

The critical failure mode is the collapse of independence. When participants stop forming their own judgments and start copying each other — when the shipper stops watching the price of tin and starts watching what other shippers are doing, you get herding. Diversity of opinion collapses. The market stops aggregating dispersed knowledge and starts amplifying a single narrative. Everyone consumes the same media source. Everyone talks to the same echo-chamber. Everyone watches the same price chart and draws the same trendlines. The signal itself becomes a feedback loop.

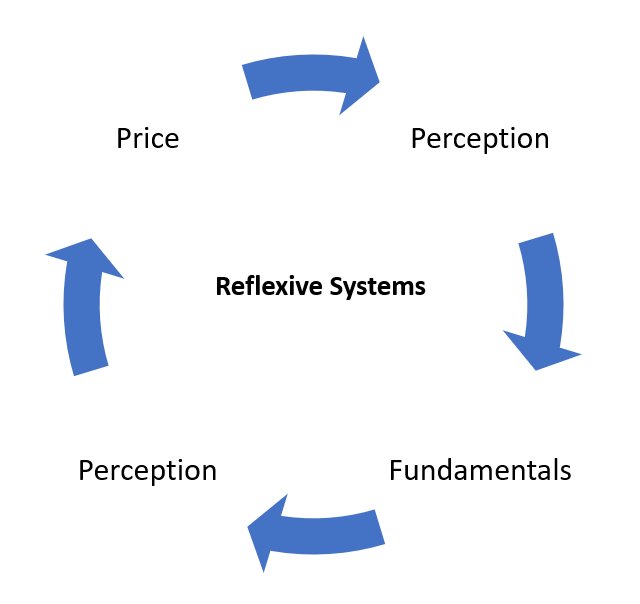

This is where legendary traders like George Soros enter the picture with his understanding of reflexivity. Soros's main insight was that unlike in the natural sciences, the objects of observation in financial markets are not independent of the observer/participant. Market participants' biased perceptions are not merely a passive reflection of reality. Rather than an efficient market, their perceptions influence the market prices itself!

When investors due to FOMO believe a stock is hot and will continue to rise indefinitely, their frantic rush to bid changes their nature from passive observation to active influence. This frenzied demand pushes the price up, which confirms their belief and attracts more buyers. It is the classic case of a parabolic chart that forms across multiple asset classes throughout financial history. A positive feedback loop forms: perception shapes reality, which shapes perception. The fundamentals became the price, and the price became the fundamentals.

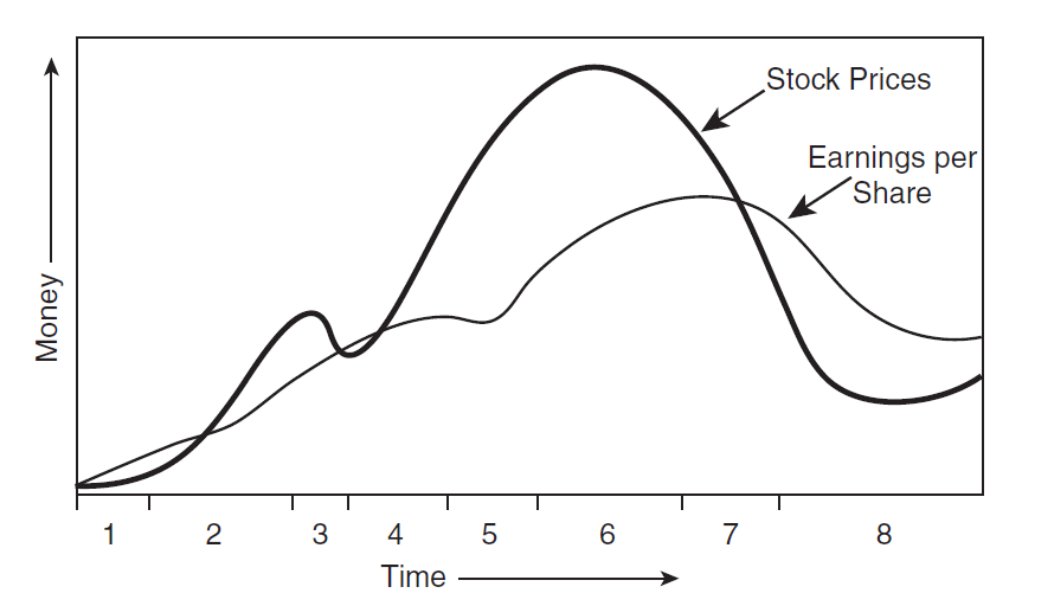

Soros calls these reflexive loops, and he distinguishes between two types of feedback. Negative feedback is self-correcting. The market overshoots, participants notice the divergence from fundamentals, and they trade against the mispricing until it resolves. This is the normal, boring state of markets. But positive feedback is self-reinforcing — the overshoot causes participants to believe the trend is real, which drives further overshoot. This is the anatomy of a market bubble.

Every bubble, in Soros's framework, has two components: an underlying trend that prevails in reality, and a misconception about that trend. The trend and the misconception reinforce each other until the gap between perception and reality becomes unsustainable. Then the loop reverses violently. The 2008 housing crisis is the canonical example: rising home prices led banks to increase mortgage lending, which increased demand for homes, which drove prices higher, which justified more lending. The reflexive loop ran until reality reasserted itself and the entire structure collapsed.

So how does the system self-regulate?

The price system is self-healing because reality is the ultimate resolution source. A reflexive loop can run for months, sometimes years, as the history of large-scale financial bubbles have shown. But it cannot run forever because, unlike the perceptions that fuel it, the underlying reality does not care about the narrative. The tin supply is what it is. The housing supply is what it is. The company either generates cash flow, or it doesn't. The election either goes one way or the other. Eventually, the price must converge on the fact.

And Taleb's ruin mechanism accelerates this convergence. The people who rode the reflexive loop the hardest, i.e. traders who bet the most on the bubble's continuation, are the ones who face the most catastrophic losses when it reverses. They hit the absorbing barrier. They're removed from the system. And with their removal, their bad information is purged from the market's signal. The correction becomes an evolutionary event that filters out the winners and losers, and the market emerges from a bubble not just with lower prices, but with a different, more battle-tested set of participants.

But this only holds if you let ruin do its work. When governments bail out the banks that should be hitting the absorbing barrier, they short-circuit this filter. The bad information stays in the system, the incompetent survive, and the next bubble builds on an even weaker foundation. It becomes a case of heads I win, tails the taxpayer loses, or what I like to call "socialism for me but not for thee".

Still, even when the filter is tampered with, the underlying logic does not change. It only takes longer and hurts us more. The mechanism bends but is fundamentally not broken.

Ultimately, Hayek explains why prices work. Taleb explains what keeps them honest. Surowiecki describes when the mechanism holds and when it breaks. And Soros, who understood all three principles via his practical wisdom and edge, got filthy rich trading the difference.

Prediction markets like Polymarket are the simplest, most elegant test case for this entire framework. They isolate a single question. They require real capital. They resolve against an objective outcome. They let us watch, in real time, whether a decentralized collection of financially exposed participants produces better forecasts than a centralized collection of credentialed experts with NOTHING on the line.

The evidence so far suggests they do. Not perfectly, and not without the structural risks that come with any emerging market — thin liquidity, platform risk, regulatory uncertainty, a dispute resolution layer that has already proven controversial, and the ever-present possibility that when Surowiecki's conditions degrade, the market will hurt you before it heals itself.

But the principle is not new. It's as old as Hayek's 1945 paper, as old as the price system and the market economy itself. Knowledge is dispersed. No one mind or central planner or authority can hold it all. The only mechanism we've found that aggregates it without centralizing it is a price formed by people who have something real to lose. That's the price of truth. It is not just the cost of participating, but the cost of being wrong.

Markets are not truth machines because their participants are honest. They are truth machines because the mechanism itself is honest. It takes your money when you're wrong, and over time, it takes everything from those who are consistently wrong, until the only people left setting the price are the ones who've survived the filter.

It is capitalism at its finest.